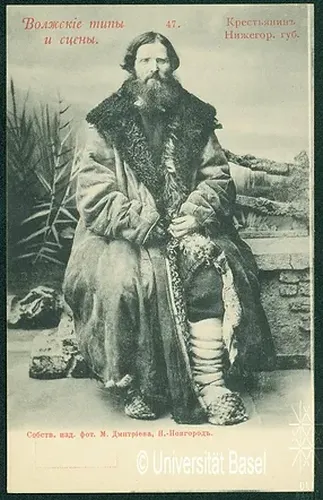

The project makes an extensive collection of Russian postcards public which is held by the Chair of Eastern European History at the University of Basel.

Full Project Description

The invention of photography and the worldwide professionalization and unification of the postal system fundamentally changed communication in the middle of the 19th century. In 1872, only three years after the first - still imageless - postcards circulated in Austria-Hungary, they were also admitted to the Russian postal system. The first Universal Postal Congress, which was held in Berne in 1874 and was followed by over 22 countries, finally unified the new medium and increasingly printed with photographic motifs from the 1880s onwards. They first made this cheap form of communication a popular mass medium. The modern postcard was born. In 1875, more than 231 million postcards were sent - by 1900 it was supposed to be 2.8 billion. However, the Russian market lagged behind this development. Due to state monopolies, which were only slowly dismantled shortly before the turn of the 20th century, foreign companies dominated the Russian market for a long time. Only slowly, but then more and more successful, Russian companies gained stable market shares - market giants such as the Swedish company Granberg had to accept the fact that companies such as the Moscow photo studio Nabholz, Scherer and Co. now offered postcards of equal quality. In addition, however, many small and local print and photo studios in particular ensured that the range of products and services offered in the Russian Empire became increasingly diverse. One example of this is the Tashkent enterprise of photographer I, who presumably came from Transcaucasia. A. Bek-Nazarov.

But postcards cannot only be read as symbols of increasingly globalized markets and international standardization processes. They demonstrate just how quickly individuals and various groups of people acquired this medium and changed it beyond its commercial or propaganda purposes: numerous cultural and social practices emerged: postcards were sent, described, scribbled, collected, exchanged, framed, destroyed or transformed into bookmarks. For example, cards with the motif of the imperial family were probably held respectfully in the icon corner - in other contexts, however, the deliberate damage to the imperial paper counterfeit expressed resistance or rejection.

At that time as well as today, ghosts and tastes differed in their different motives and dressings - and in some cases even aroused national pride or the professional honor of the viewers: The Russian photographer Sergei Prokudin-Gorskij, who himself published postcards in St. Petersburg, remarked during a stay in Central Asia:"Today I bought a postcard of the city of Samarkand. The seller told me with some pride that the letter had been printed abroad using a photographic method, as if it was impossible to make such a reproduction in Russia. This may be partly true - but I have seldom seen such bad pressure, not even in miserable printing houses - but this was a special case."

Examples such as these are the examples that demonstrate the source value of the medium for modern history studies by pointing out a purely art- or technology-historical reading of this source, which up to now has mostly been understood as a serial source, and by suggesting the individual material biographies of individual pieces or social practices of certain actors that can be interpreted in terms of cultural history.

For this reason, the Chair of Modern and Eastern European History at the University of Basel has decided to make its collection of postcards from the Russian Empire accessible to a broad public.